How to Submit a World Record Fish…

You caught a world record fish. Congratulations!

Given there are 35,000 described species of fish and counting, getting a world record is not quite as difficult as you’d think. Sure, only about half of those species reach the 1-pound minimum weight required for a world record, but that still leaves you about 17,500 potential records — likely more options than your dating pool.

There are several kinds of records to consider. The All-Tackle World Record is the real world record, that is, the biggest specimen of a species documented according to International Game Fish Association (IGFA) rules. These are the only ones that I personally care about. There are also Line-Class Records (largest fish caught on a certain weight of line), All-Tackle Length Records (longest fish recorded but not heaviest), and Small-Fry Records (for kids). Again, the All-Tackle Record is the largest fish caught according to IGFA rules, and it’s the only one I care about, but you do you.

So you’ve caught a potentially record fish. What now? Theoretically, you would have done some legwork beforehand, but even if you didn’t, you can still claim the record. Here’s how.

My First Record

I’ve been tracking every fish I’ve caught since 2004, so I can tell you that by fall of 2016, I’d already caught three world records (Calico Surfperch, Deacon Rockfish, Redtail Surfperch) without realizing it. Since I didn’t properly weigh, measure, and/or photograph them nor save the required line sample, I couldn’t submit them. Cue symphony of the world’s smallest violin. It’s all good, though. In November of 2016, I had another opportunity.

For some reason, bored of catching just trout and crappie and carp, I decided to try and catch 75 species of fish in 2016, employing the hashtag #75Species2016. I didn’t even come close (I was fishing entirely in Oregon waters, hadn’t started microfishing yet, and didn’t take any saltwater charter trips), but it really got me interested in species fishing. I also started using my #SpeciesQuest hashtag after getting into Steve Wozniak’s species fishing blog early in the year.

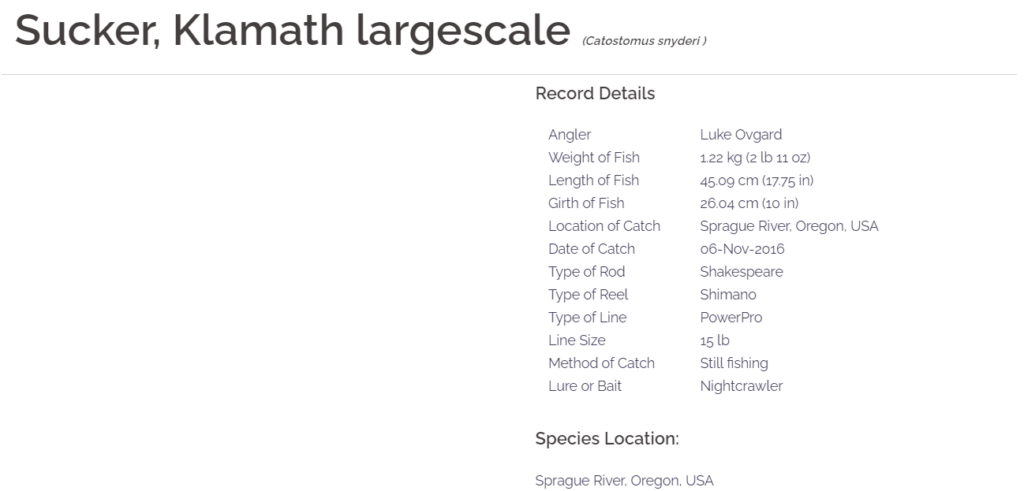

Late in 2016, I caught the only officially documented Klamath Largescale Sucker in at least 20 years. It was obviously a new species for me, but given that it hadn’t been caught, I knew it was also a world record, assuming I could check all of the boxes necessary for the IGFA record application. Odds are, other had anglers caught them — probably even the same year I had — but given that the much more high-profile Shortnose Sucker looks very similar to the Klamath Largescale Sucker, those Klamath Largescale Suckers went undocumented.

Unlike the other suckers found in the Klamath Basin, Klamath Largescale Suckers are not Federally Endangered; they’re completely fine. It’s tough to distinguish them from Shortnose Suckers, though, so harvest of any sucker in Klamath County is illegal.

I knew this, but there was nothing wrong with measuring and photographing it, so that’s what I did. I was fishing on a ranch with access to the Sprague River with my friend, Ben Fry. We were soaking bait for Yellow Perch, and the bite had been slow. We’d caught a few perch, as well as a few small trout, but when I landed my sucker, it was the highlight of the day. For me, at least.

At the time of the catch, I knew IGFA required a few things, so I got to work, leaving the fish submerged in the icy river inside the net while I gathered my scale and cloth tape measure. I’d been prepared, and it paid off. I immediately emailed Steve Wozniak, whom I’d never contacted before, and I asked him if he could help out a longtime reader. To my surprise, the man who’s caught more species of fish than anyone else in history replied immediately and walked me through it.

It took a few months, but eventually, I’d logged my very first world record (and the one least likely to ever be broken), for a Klamath Largescale Sucker.

Preparation

In order to claim a potential world record, you have to do some legwork ahead of time. Here’s what you should do before you ever even wet a line:

1) Review IGFA’s World Record Rules. Most are simple ethics you already have as an angler, such as not snagging fish, using dynamite, or cast nets.

2) Research which records are vacant. These are the easiest to beat. A vacant record is one where no fish over a pound caught according to the rules has been submitted. If your fish exceeds a pound, and the record is vacant, it’s eligible for submission. It will almost definitely be broken if the fish grows much larger than a pound, but at least you’ll have the record and get your 15 minutes of fame.

3) Research which records are filled but beatable. Many of the records barely meet the minimum and grow much larger than the current record. A record doesn’t mean that fish was the largest specimen ever caught; it just means the largest caught legally on hook and line and actually submitted. Many people catch records and assume the record is bigger than their catch, so they don’t submit. This is a mistake.

4) Make sure your gear meets IGFA standards. Biggest thing is the number and type of hooks. No more than two single hooks for bait and no trebles for bait fishing. No more than three hooks for lures (they can be single, double, or treble hooks).

5) Pre-certify your scale. It costs $50, and it’s good for a year. Most people who say they don’t mess with records do so with the excuse that they don’t want to kill a fish to weigh it on a permanent certified scale. Good news. You don’t have to kill the fish if you certify your own portable scale. I’ve released all but one of my records unharmed (one was an invasive I killed in compliance with state law).

When You Catch It…

Obviously, practice good fish handling if you plan to release the fish. Record fish do not have to be released, but catch and release is always encouraged.

1) Take a clear picture of you with the fish. Both the fish and you should be identifiable (take off your mask or sun shield). Hold the fish horizontally if you plan to release it.

2) Measure the total length, fork length, and girth of the fish.

3) Weigh the fish on land. If you’re on a boat, this means putting the fish in the livewell or killing it (if you plan to eat it) and returning to shore for the measurement. Weights on a boat don’t count. Keep in mind that killing a fish, bleeding a fish, and/or removing it from the water will cause a negligible decrease in the fish’s weight, and it’s land-based weight is what matters.

4) Save the entire leader and 5 meters (16.5 feet) of the mainline. IGFA will use this for line testing. It’s a bit inconvenient, but required. I’ve wrapped line samples around a water bottle, a piece of cardboard, or whatever is available. You don’t need to include the hooks or lure if you take a clear picture of that part of your rig, but you can send in the hook/lure if you choose to. You won’t get it back. The line sample is definitely the most difficult part of the application, and it’s not that difficult.

5) You don’t need a witness, but if someone watched you catch it, get their contact information. It will only help you.

6) Taking a catch or release video and additional pics of the fish for identification purposes will only help your cause, but they’re not required.

When You Get Home…

My first record was caught on an afternoon trip an hour from my house, but I’ve also caught records on longer road trips and in locations far from home. Keeping good records is essential regardless.

1) Gather all of your measurements.

2) Take a picture of the hook/lure, rod, reel, and net or gaff (if applicable). You’ll have to upload these later.

3) Measure the length of the rod from the center of the reel seat to the tip (tip length) and the center of the reel seat to the butt (butt length). You’ll need these measurements.

4) If your scale wasn’t certified prior to the catch, you’ll have to send it in IGFA with your line sample. Include $50 to get it certified (the certification lasts a year). If it was weighed on official scales at, say, a dock or bass tournament, record the contact info of the Weighmaster. Regardless, take a picture of the scale used. You’ll have to upload it later.

5) Measure your leader. Include all of it along with 16.5 feet (5 meters) of your mainline. I like to tape one end to a stiff piece of cardboard and wrap it around the cardboard, taping the end. Write your name and the species on it to make processing easier.

6) If your fish is one not easily recognizable, getting an ichthyologist or fish biologist to verify its identity is a good idea. It’s not required, but it will help your case and speed your application along.

7) If you use the online application (definitely use the online app; it’s way easier), you won’t need wet signatures or a notary. This is a recent change, and it makes the process way simpler.

8) Proceed to the IGFA World Record Application. You could print it and mail it, but don’t. Do it online. It’s infinitely easier. Use the walkthrough below if you get stuck.

IGFA World Record Application Walkthrough

Go to the IGFA website and create an account. Membership is $50 per year for an individual, $75 for a family, $30 for anyone under 18, or $1500 for a life membership. In addition to the annual membership fee, there is a $50 application fee per world record application. Don’t complain. If the government managed records, you’d be paying far more than $50 per application in taxes.

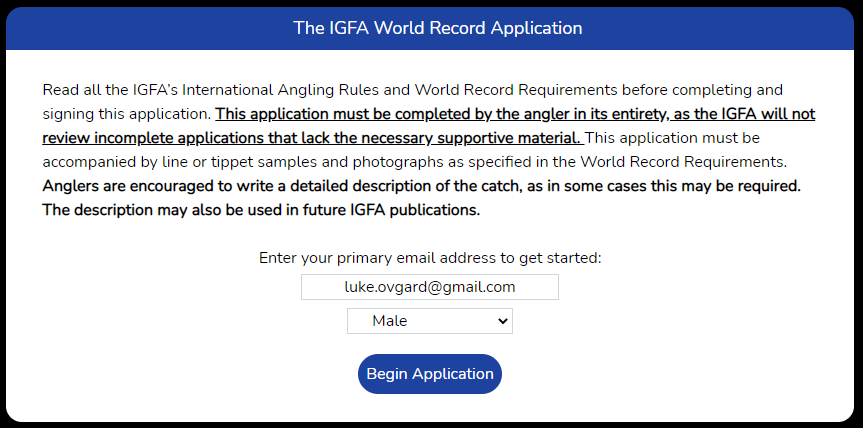

Once you have your account, proceed to the online IGFA World Record Application.

1) Put in your email and gender and click “Begin Application” to proceed.

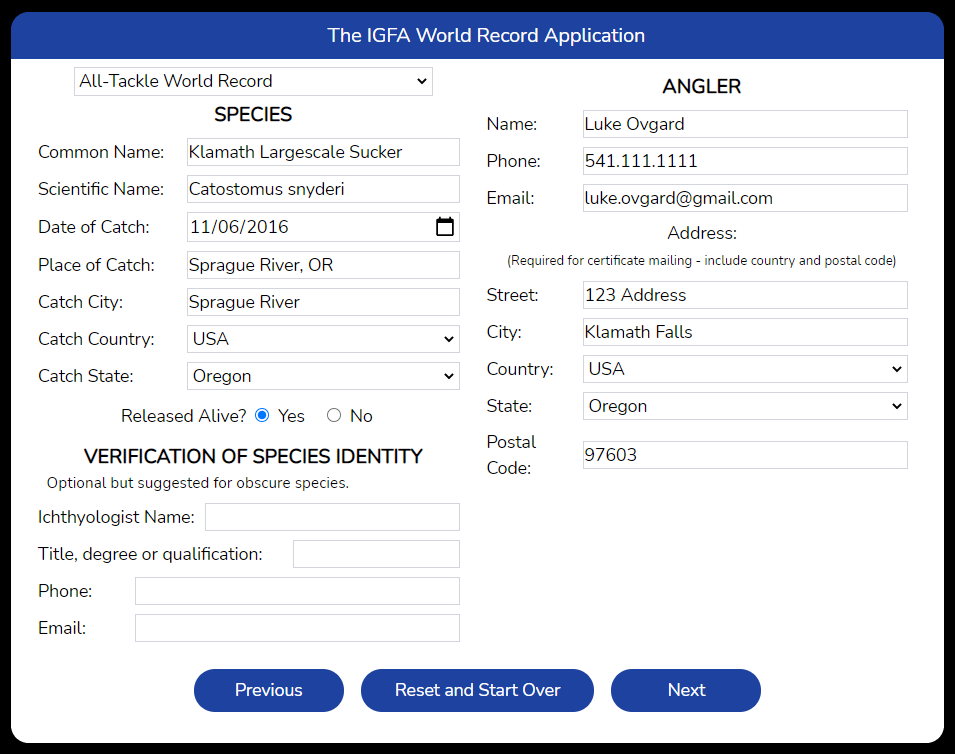

2) Fill in the details of your catch. If the record is vacant, type the Common and Scientific Names. If there’s an existing record, the application should populate it for you. Fill in all other relevant details. Everything on this screen is required, except for the VERIFICATION OF SPECIES IDENTITY section, which is still encouraged — especially for obscure species.

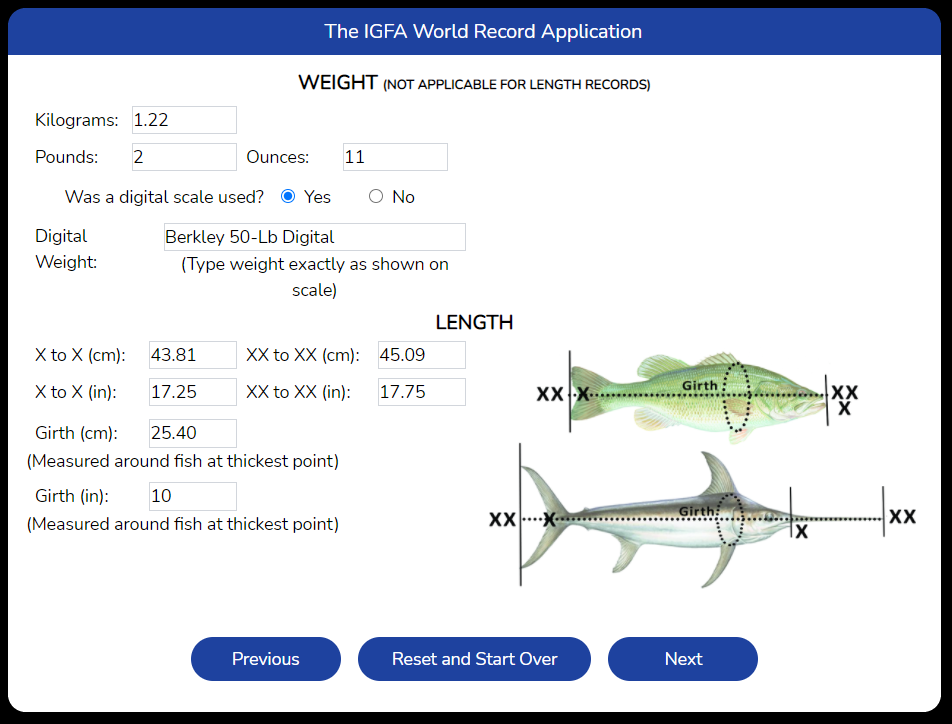

3) Input your measurements. The XX length is total length; X length is fork length. Some species (i.e., eels) don’t have forks. Put the XX length twice. Others (i.e., Barramundi) might have a convex fork, where the fork length is actually longer than the total length. Still record it. Be sure you use either centimeters or inches in the appropriate boxes.

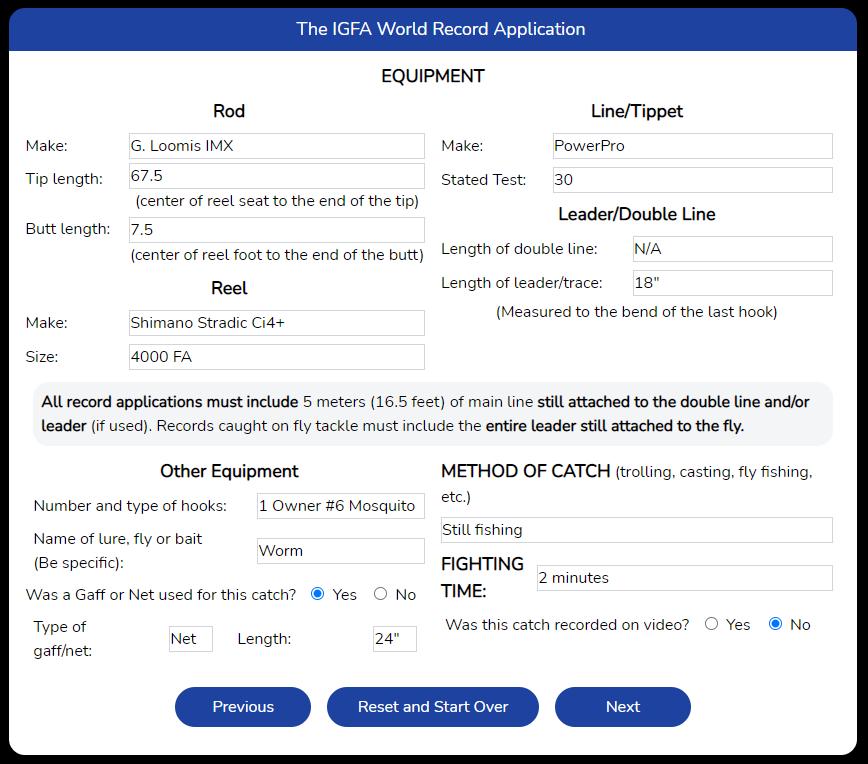

4) Time for the details of your equipment. Be as specific as possible here for all gear. You can estimate fight time.

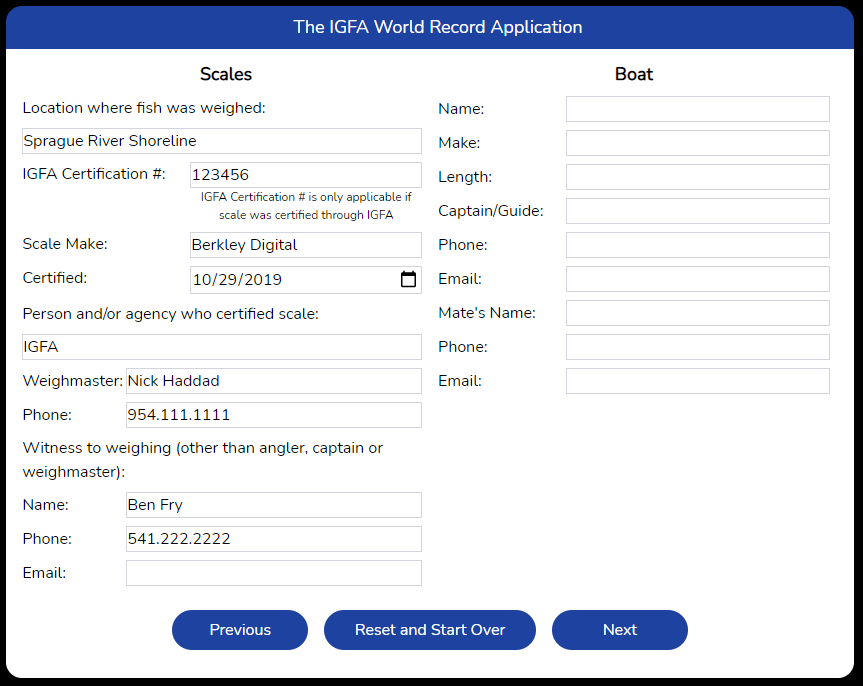

5) If you weighed the fish on a portable scale, note that. If it was already IGFA-Certified, include the Certification Number. If not, you can mail it in with an extra $50 (good for a year) to get it certified. If you weighed it on public or commercial scales, record the Weighmaster’s name and Contact Info here. If a third party witnessed the weigh-in, record it. If not, no worries.

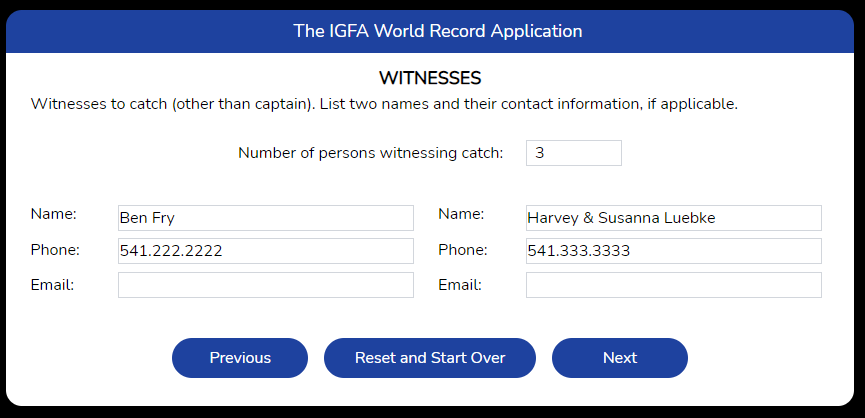

6) You do not need a witness. It helps your case, but proper photos will be fine. I happened to have three witnesses for my first catch, all of whom I knew, so I included contact info. If you don’t have a witness, leave this page blank.

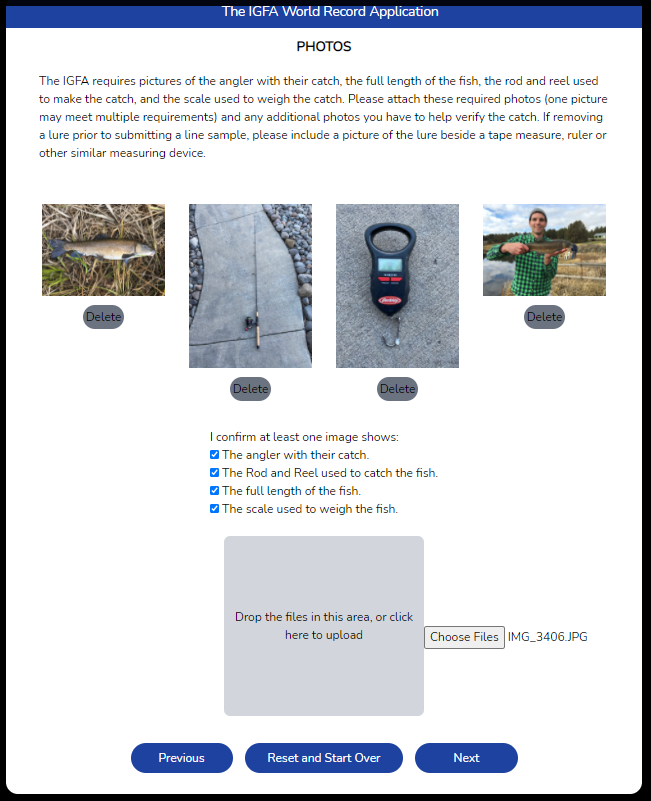

7) Next come pictures. At a minimum, you’ll need a picture of you holding the fish, a picture of the rod/reel, and a picture of the scale. It’s not a bad idea to include detail shots of identifying features for the fish if it can be easily mistaken for a similar species. You can also include videos of the catch. In some cases, I’ve submitted as few as three photos. In others, I’ve submitted six or seven plus a video.

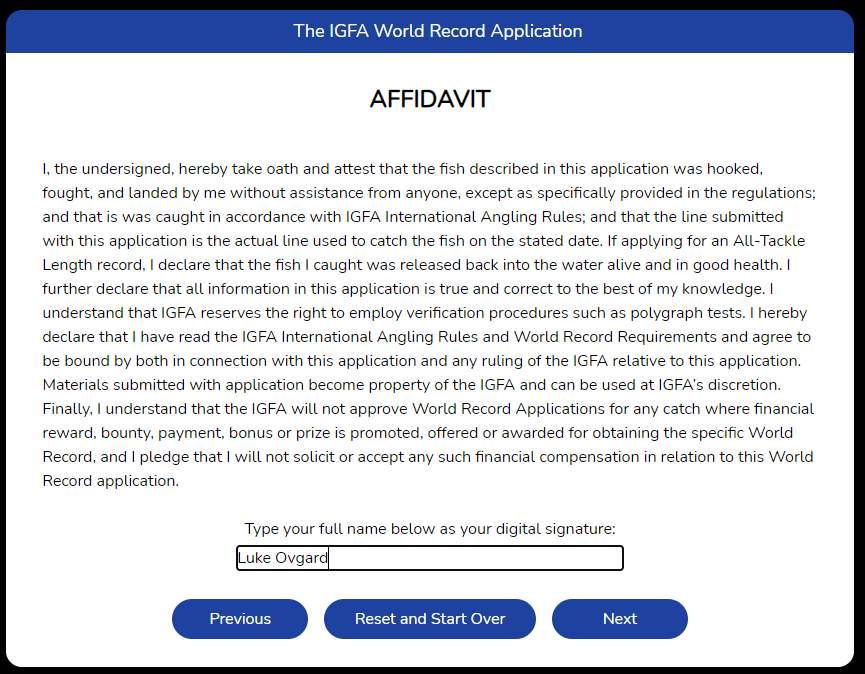

8) Finally, sign the form digitally. You used to have to get wet signatures and then notarize the app. Once again, online is infinitely simpler. Once you hit “Next” on this screen, you’ll be prompted for payment. Pay your $50 for the application (plus $50 for the scale and $50 for the annual membership if you haven’t done so already). Again, the membership and scale certification are good for a year, so you can submit multiple records on one scale certification.

9) Once you’ve completed the app, mail in the line sample. If you need to get your scale certified, you can include it with the line sample or samples. Remember to write your name and the species on each line sample. If you’re submitting line samples for multiple records at once, you can use the same envelope.

Send line samples to:

IGFA World Records

300 Gulf Stream Way

Dania Beach, FL 33004

The line samples/lures/hooks will not be returned to you. If you opt to certify your scale at the time of application submission, it will be returned.

10) Depending on how thorough your application was and how much legwork (such as fish identification) you did yourself, processing times can vary. I’ve had records approved in under a month, but I’ve also had records take up to six months. You might get an email from IGFA, so be prepared to answer questions if they arise.

Record Lookup

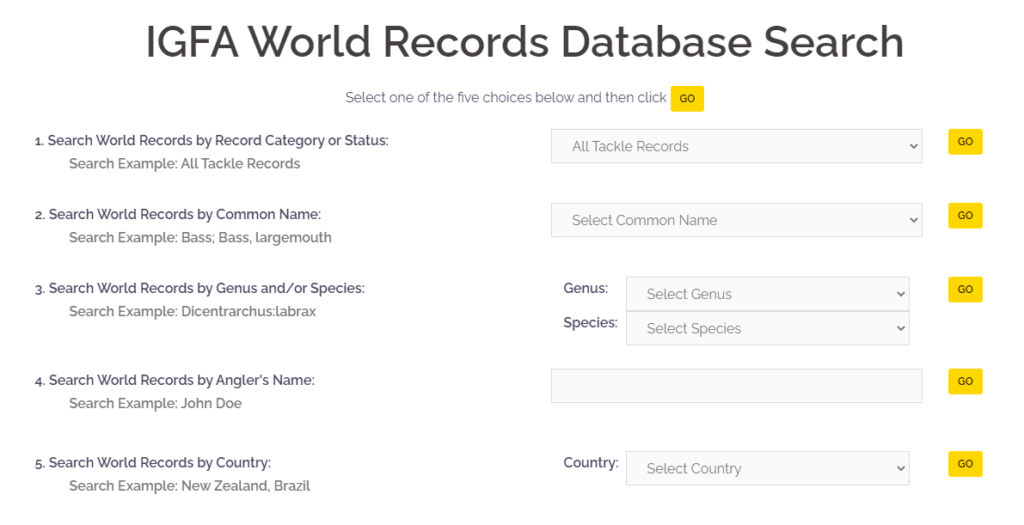

You can look up records in the IGFA database a number of ways. I prefer the Common Name search, but you do you.

One cool feature is that once you have a record to your name, you can search for all the records you have. All told, I have eight world records. Five are listed on the site (one is Retired, or beaten), while three are still pending. Nonetheless, it’s always cool to see your name next to a record.

Once your record(s) gets approved, you’ll receive a certificate in the mail, and you’ll be able to view your own record(s) online. Congratulations! You now have a world record to your name! Flex accordingly.

If you found this helpful, please support my writing and allow me to do more projects like this. You can subscribe to my weekly column for just $1 per month. Just a buck. Please subscribe by clicking “Become a Patron” below.